In this post, I’m featuring a new resident on the Landing Book Shelves, a Christmas gift no less. The book is the Birmingham Art Book: The City Through the Eyes of its Artists edited by Emma Bennett (who also created the cover art and wrote the preface). Joe Lycett has contributed a foreword, setting the tone for the book by declaring, ‘Birmingham, as I’m sure you’re aware, is the best city in the world. And the art here is the best in the world too.’

This book is the seventh title in a series of city art books published by UIT Cambridge Ltd. I hadn’t come across this series before, but I notice that Dublin and Edinburgh are included, so I might have to explore further. If you remember, I did a post some while ago about the Silent Traveller in Edinburgh, so I am following a favourite city theme here. It could build into a whole new sub-collection (as if I needed another one).

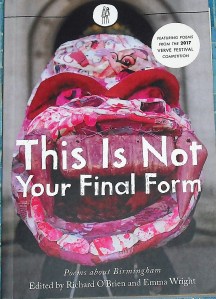

The Birmingham Art Book features the work of sixty-one artists, some having more than one piece included creating a collection of wonderful images of the city. The views included here are depicted in a wide range of styles and media, giving the collection a very vibrant feel. It’s a book for dipping into over and over again as each time you browse the images, another detail from the Birmingham landscape is revealed. I’m a Brummie born and bred and despite having moved away years ago, I do go back to visit regularly. This book is a lovely souvenir to have, a reminder of all the myriad buildings, parks and features that make up the city. It’s also a very nice addition to my Brummie collection. I haven’t added to it since buying This is Not Your Final Form, a poetry collection from Emma Press.

But of course, I never get chance to mooch around the city as much as I would like. I therefore found that the book’s city depictions had a huge nostalgia value for me. I kept spotting things that made me exclaim, ‘Ooh, I remember that!’ However, I have also been scratching my head at other images, not being quite able to place something that I feel I ought to remember. I’m also reminded of places that I haven’t re-visited in ages, such as the Barber Institute and the Electric Cinema.

It is nice to see that the suburbs get a look in too. More nostalgia here; Cadbury’s, Kings Heath, Moseley and Cannon Hill Park. There are so many great images in this collection that it would be hard to pick out a shortlist of favourites. I will just name check a few though I could easily end up listing the entire contents:

- I smiled at the close-up depiction of the gargoyles on St Martin’s Church looking with what seems to be an expression of amazement at the Selfridges Building (Graham Leonard King).

- Robert Geoghegan’s picture of Cannon Hill Park full of Canada Geese. The tagline on the painting reads: ‘Today:Cannon Hill Park. Tomorrow: The World’. I also like his portrait of ‘Old Joe’ at the University of Birmingham, The Owl and the Clocktower. I love the owl!

- Alexander Edwards (Brumhaus) has a graphic-style view of the Jewellery Quarter, especially pleasing to me, as I was around that area for the first time in ages before Christmas.

- I include in my picks a couple of city centre views, as I was busy spotting buildings that I recognised: Bird’s Eye New Street by Chris Eckersley and Memories of Birmingham by Martin Stuart Moore.

- And finally, a mention for the travel poster/Art Deco inspired peices by Milan Topalović. The view of China Town is gorgeous.

- And finally, finally let’s not forget the differing depictions of the Library of Birmingham, the Rotunda, the canal scenes, the Floozie in the Jacuzzi, The Bull and the Grand Central.

Highly recommended to Brummies past and present! Go out and buy one (and no, I’m not on commission).

You must be logged in to post a comment.