As I mentioned previously I’m continuing with my Russian theme by reading Doctor Zhivago (Boris Pasternak) which I had for Christmas (it seems ages ago now!) In keeping with my usual mode of practice, the good doctor has had to give way to a couple of other reads, including Nancy Mitford, Andrés Neuman and Kader Abdolah but I do keep returning to him after straying.

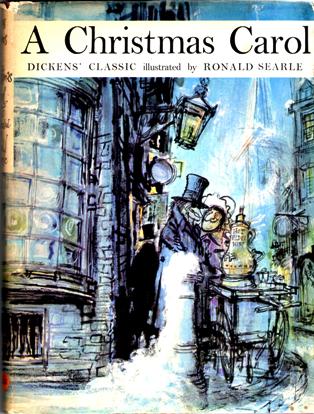

My Christmas Present…

Finally, I have reached the home straight in Doctor Zhivago, the penultimate chapter, at which point the revolution has the country in its tenacious grip. Life is ruled by committees and many, many regulations which it is not safe to ignore. Yuri Zhivago, now living once more in Moscow has seen his life change immeasurably by war and revolution. He has suffered hunger, violence and fear as well as experiencing great passion, as he became caught up in his nation’s struggle to throw off centuries of Tsarist rule. Given that Putin‘s Russia is so much in the news lately it has proved to be an appropriate time to read about the course of events that would eventually lead to the present political landscape.

As usual in my posts, I am trying to avoid plot spoilers but in this case, I think it is highly likely that many of you will have at least seen the film version (possibly more than once) so the broad outline of the plot will already be familiar. To many people I’m sure, Omar Sharif will always be Yuri and Julie Christie, Lara (Larissa) no matter how many times they may read the book. Apart from ‘Lara’s Theme’ and Sharif’s melting eyes my abiding memories of the film are the ambiguous personalities of Strelnikov (Lara’s husband Antipov) and Yevgraf (Yuri’s half brother) played by Tom Courtney and Alec Guinness respectively. And lots and lots of snow covering the Russian landscape against which Yuri’s wife Tonya (Geraldine Chaplin) appears luxuriously swathed in furs.

The strap line on the cover of my edition of the novel declares that Doctor Zhivago is ‘One of the greatest love stories ever told’ but there is much more to the book than that. The novel spans a period of intense upheaval in Russian history, as experienced by Yuri Zhivago, his family and friends. There is a huge cast of characters apart from those I’ve mentioned above, who participate in the momentous events described in the book. Yuri encounters people from different factions during the course of the book, some of whom he meets more than once during his various ordeals. Sometimes it seems to stretch credibility that so many coincidences of meeting seem to occur to Yuri, but overall I didn’t find that this detracted from the novel. Rather it created a sense of life not being lived in a neatly linear way; links between people who are not always apparent on the surface that affect our lives.

Italian First Edition

The plot teems with life and death and it gives the reader a fascinating insight to the terrible realities of the struggle between the Whites and the Bolsheviks after the carnage of World War I. Pasternak was writing from a position of uncertain safety since he had fallen foul of Stalin’s regime to the extent that his book could not be published in his own country. The manuscript was eventually smuggled to Italy for publication. The translators of my edition, Max Hayward and Manya Harari (1958) pay tribute to Pasternak’s poetic prose style fearing that they haven’t done justice to his use of language.

Here is a passage from early on in the novel when Yuri’s wife Tonya has just given birth to their first child:

Raised higher, closer to the ceiling than is usual with ordinary mortals, Tonya lay exhausted in the cloud of her spent pain. To Yuri she seemed like a barque lying at rest in the middle of a harbour after putting in and being unloaded, a barque which plied between an unknown country and the continent of life across the waters of death with a cargo of new immigrant souls. One such soul had just landed, and the ship now lay at anchor, resting in the lightness of her empty flanks. The whole of her was resting, her strained masts and hull, and her memory washed clean of the image of the other shore, the crossing and the landing.

I think the translators certainly did justice to one of the most moving passages on childbirth that I have ever read. Having said that, my grammar checker insists that the first sentence is a fragment and needs revising…proof if it is needed, that it’s not always wise to listen to machines…

I’ll be finishing Doctor Zhivago in a day or so (provided that I can pass the ‘Quick Pick’ shelf in the library without looking) and I will need to make a decision about the next Landing Book Shelves read.

More on that soon but meanwhile do drop me a line below or on Twitter if you have any challenging suggestions…

You must be logged in to post a comment.