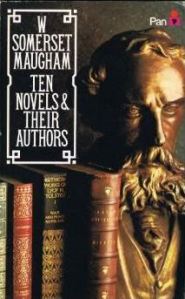

I have been reading some of the literary criticism essays in Somerset Maugham’s book (mentioned in a recent post), beginning obviously enough with those about books that I have read. First, I turned to the essay on Emily Bronte and Wuthering Heights for the simple reason that I read Wuthering Heights so many years ago that it is probably due for a re-read. This essay seemed like a good way to begin to re-acquaint myself with both the book and the author. It also inspired me to dig out my copy of the Brontë family biography by Juliet Barker (1994).

I have been reading some of the literary criticism essays in Somerset Maugham’s book (mentioned in a recent post), beginning obviously enough with those about books that I have read. First, I turned to the essay on Emily Bronte and Wuthering Heights for the simple reason that I read Wuthering Heights so many years ago that it is probably due for a re-read. This essay seemed like a good way to begin to re-acquaint myself with both the book and the author. It also inspired me to dig out my copy of the Brontë family biography by Juliet Barker (1994).

Several writers have presented their views of the Brontë family since Somerset Maugham wrote his essay (1954), but Juliet Barker’s book, simply called The Brontës (1994) promises to be the definitive account. I somehow managed to miss a revised edition that came out in 2012. Perhaps I will give myself a very late Christmas present (I still have a voucher to spend) and upgrade my original copy. Meanwhile, it was interesting to see what Maugham made of Emily Brontë’s personality from the available sources. He did point out that to be able to talk about Emily; he needed to go back to her father’s origins and to approach Emily through her family, as she is difficult to know. Maugham’s portrayal of Patrick Brontë is much more negative than Barker’s image. She has painstakingly reconstructed hers from evidence culled from newspaper and church archives about Patrick’s political activities and presented a less one sided view.

It might seem obvious but the main fact to bear in mind when reading biographies about authors (or indeed any historical person) is that time and fresh documentary evidence often reveals a different picture. In some respects, that is not strictly true of Emily Brontë since she left very little personal testimony and apparently had no friends so there is a lack of social correspondence. Apart from her poetry, juvenilia and her only novel, evidence is indirect. However, over the years a much clearer picture of the whole family has emerged due in particular to Juliet Barker’s diligent archive research, which illuminates Emily’s character as far as it is possible to do so.

Here is a description of the fifteen-year-old Emily taken from Maugham’s essay, quoted here in full, as it seemed a shame to cut it short. Though he does not give the full reference, it was taken from the earliest biography of Emily by Mary Robinson, which was published by W.H. Allen in 1883 (I found this reference in Barker’s sources).

a tall, long-armed girl, full grown, elastic as to tread; with a slight figure that looked queenly in her best dresses, but loose and boyish when she slouched over the moors, whistling the dogs, and taking long strides over the rough earth. A tall, thin, loose-jointed girl – not ugly, but with irregular features and a pallid thick complexion. Her dark hair was naturally beautiful, and in later days looked well, loosely fastened with a tall comb at the back of her head; but in 1833 she wore it in an unbecoming tight curl and frizz. She had beautiful eyes of a hazel colour.

She was clearly an active girl, who loved the outdoors, perhaps one who would have been impatient with the restricted life of a well brought up lady. Physically she must have been what is often termed handsome, rather than conventionally pretty. Clearly, she ‘scrubbed up well’ as the saying goes. Emily was apparently painfully shy with anyone outside the family circle and Maugham quotes from Charlotte Brontë’s letters to show that the sisters at times had a difficult relationship. After learning from Juliet Barker that few writers have quoted from Charlotte’s original letters, using instead unreliable published ones, I am sceptical of Maugham’s conclusion, “One is inclined to think that Charlotte never knew her sister”.

It is illuminating to consider the different approaches to studying the Brontë family and Emily in particular. Due to the lack of straightforward biographical evidence, many writers have tried to find the real Emily through her writing. On the other hand, Juliet Barker considers it misguided to use literary criticism. As she says in her introduction, “Trawling through the Brontës fiction in search of some deeply hidden and autobiographical truth is a subjective and almost invariably pointless exercise”. She also rather scathingly refers to “theories of varying degrees of sanity” earlier in her introduction. I assume that she places in that category the theory, to which Maugham and other literary critics subscribe, that Emily Bronte was a lesbian. As far as I can recall, as it’s been twenty years since I read Barker’s biography, she doesn’t suggest this possibility from her study of contemporary sources.

One of the biggest myths that grew up around the Brontës was that they lived very harsh and isolated lives in a lonely moorland house. Maugham doesn’t perpetuate this idea, as after he visited Haworth, he described the house as situated at the top of a hill, “down which the village straggled”. However, he does mention that there was a graveyard on both sides of the parsonage, which some folks (but not perhaps curates) may have considered being a gloomy location. He also pointed out that the mood of the moorland varied with season and would not always have been wild and bleak. Indeed, he described his visit thus,

The countryside was bathed in a haze of silver-grey so that the distance, its outlines dim, was mysterious. The leafless trees had the elegance of trees in a wintry scene in a Japanese print, and the hawthorn hedges by the roadside glistened white with hoar frost. Emily’s poems and Wuthering Heights tell you how thrilling the spring was on the moor, and how rich in beauty and how sensuous in summer.

I didn’t find the location particularly bleak either when I was there a few years ago, and the house was solid and pleasant looking, though of course it would have been cold in winter without central heating. However, the Brontë sisters’ lives would have been no harsher than for any other country curate’s family in the nineteenth century. They could obviously afford a servant (Tabby Ackroyd) to help around the house. Emily helped with domestic chores, and I liked the image of her kneading bread with a book propped up in front of her as she worked. Industrious yet slightly impractical: (turning pages with a floury hand?)

The fact that Maugham included Wuthering Heights in his ten most important novels, despite asserting that it is very badly written, intrigued me. Maugham is critical of the construction of the novel (fitting two sets of events and characters into a unit) and the unrealistic dialogue that Emily gives Nellie Dean to say. However, his verdict is that, “It is a very bad novel. It is a very good one. It is ugly. It has beauty. It is a terrible, an agonizing, a powerful and a passionate book.” He discusses the unevenness of the novel and the reasons why Emily might have chosen to tell the story in the way she did, instead of perhaps choosing a first person narrative. He felt that she wanted to distance herself from events, in effect to in hide her from the passion. His reasons? Somerset Maugham’s theory located Emily as both Cathy and Heathcliff, “I think she found Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw in the depths of her own soul. I think she was herself Heathcliff, I think she was herself Catherine Earnshaw”.

Now I do really need to read it again…let me know what you think! Drop a line in the comment box.

You must be logged in to post a comment.