I was all prepared to give the readers of The Landing blog my thoughts upon reading Vanity Fair, when one of the minor female characters, Miss Pinkerton, side tracked my intentions. I ended up delving into Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and Wikipedia for a bit of research into Thackeray’s historical allusions relating to the character. Finally, I came to the conclusion that this particular Thackeray creation bears a startling resemblance to a formidable maiden aunt in one of my favourite children’s stories.

Now read on….

Vanity Fair opens in the Pinkerton Academy for Young Ladies, when two of the main protagonists in the story are preparing to leave for the wide world. The two girls were Amelia Sedley and Becky Sharp, but for me, the redoubtable principal Miss Barbara Pinkerton (an ‘austere and godlike woman’ who was ‘as tall as a grenadier) stole the opening chapter. She is shown here parting from Becky Sharp, her least favourite pupil, who has the audacity to address the principal in perfect French:

Miss Pinkerton did not understand French; she only directed those who did: but biting her lips and throwing up her venerable and Roman nosed head (on the top of which figured a large and solemn turban), she said, ‘Miss Sharp, I wish you a good morning.’ As the Hammersmith Semiramis spoke, she waved one hand by way of adieu, and to give Miss Sharp an opportunity of shaking one of the fingers of the hand which was left out for that purpose.

That was the second time that Thackeray referred to Miss Pinkerton’s affinity with Semiramis, the first being at the opening of the chapter, where we are told ‘that majestic lady: the Semiramis of Hammersmith’ had been a friend of celebrated literary luminaries Dr Samuel Johnson and Mrs Hester Chapone. Now, I have to confess that I had only a vague recollection that Semiramis had been a queen or possibly a goddess of some sort, hence the dive into Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. The entry describes a legend about a woman who was the daughter of the goddess Derceto and an un-named Assyrian who went on to marry Ninus, King of Assyria. Brewer points out that this and many other legends grew up around a real Assyrian princess who lived circa 800 BC.

I assumed that Thackeray was comparing his redoubtable principal to the historical princess (who married King Shamsi-Adad V of Assyria), rather than the mythological Semiramis, but it is hard to say. Murder and suchlike heinous goings on were some of the activities of the legendary queen, so maybe it was a bit of a stretch to use her as a role model. However, the real Semiramis (ruled 810-806 BC) according to Vicki León in Uppity Women of Ancient Times was quite a strong capable ruler so perhaps she is a more likely source. The illustration from this book portrays the queen in soft woman-hood mode, so I can’t see her as an indomitable leader, but apparently she was. Apart from the questionable claims that she invented trousers for women and chastity belts for men, Semiramis achieved great things:

Under her leadership, a new system of canals and dikes irrigated the flatland between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, and the twin cities of Nimrud and Nineveh became the bright lights of Assyria. A true power player, Semiramis led military expeditions against the Medes as far afield as India, and forged tactical alliances as far west as Turkey.

Perhaps we may safely assume that Miss Pinkerton ran her school with the authority, determination and majesty of an Assyrian Queen. The mythological Semiramis was rumoured to have slept with her son after her husband’s death, which would not have been at all a respectable thing for a principal of a select girls’ school, especially since Semiramis had put Ninus to death in the first place. I cannot help wondering if this was a joke on Thackeray’s part. Would his readers have been aware of the two aspects of Semiramis I wonder? She was obviously as proud as any queen, but I presume that contemporary readers would have been familiar with the Semiramis comparison.

I also gleaned from Brewer’s Dictionary that a couple of European female monarchs were honoured with the nickname ‘Semiramis of the North’. One of these was Catherine II of Russia, (1729-1796) whose deeds were a little murky; the other was Margareta of Norway, Sweden and Denmark (1353-1414) who seems to have been a capable ruler, without the vexatious tendency to murder her relatives. Clearly, Miss Pinkerton is one of a very select band of inspiring rulers whose achievements know no bounds.

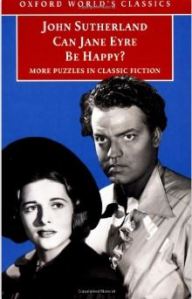

Talking about inspirational, magisterial rulers, I will finish by bringing you a wonderful creation from

Russell Hoban, brilliantly illustrated by Quentin Blake, called Miss Fidget Wonkham-Strong. This is the character I mentioned in my introduction. I am sure that you will see instantly her kinship with both the aforementioned school principal, Miss B Pinkerton and Queen Semiramis herself. As I was reading Vanity Fair, Blake’s drawing of remarkable Aunt Fidget popped into my head and wouldn’t go away. Hoban describes her thus, ‘She wore an iron hat and took no nonsense from anyone’. She was as assured of the benefits of regular reading of the Nautical Almanac as Miss Pinkerton was of Dr Johnson’s Dictionary. However, I do hope that Miss Pinkerton never said ‘Eat your mutton and your cabbage-and-potato sog’ to her pupils, or fed them with greasy bloaters as Aunt Fidget was fond of doing.

I seem to have come some distance from Thackeray, via an Assyrian Queen and Quentin Blake, but I hope you enjoyed the journey!

Credits: additional images from Wikipedia, with thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.